A Maltese Mistake, an Ottoman Plan: The Spark of War

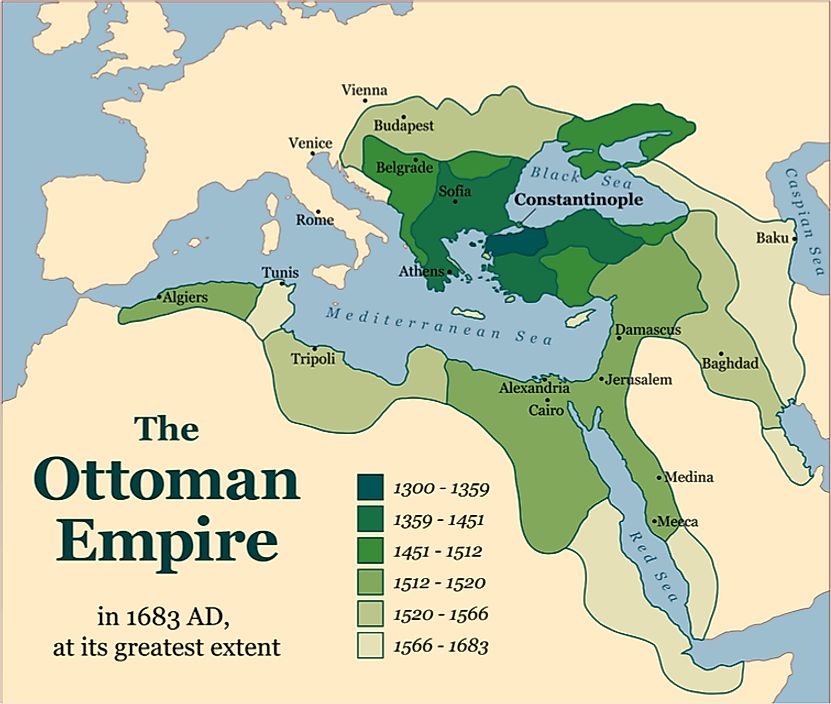

Conquering an island like Crete requires more than brute force—it demands cunning. And in 1645, the Ottoman Empire found its opportunity in the form of a disastrous mistake made by the Knights of Malta.

It began when a Maltese ship patrolling the Mediterranean captured an Ottoman vessel en route from Istanbul to Mecca. Onboard were Muslim pilgrims—including Sultan Ibrahim’s wife and son, accompanied by their eunuch. The ship was taken to Malta, and from there, events spiraled out of control. The Sultan’s wife died in captivity, the eunuch was executed, and his young son was baptized into the Dominican Order. The remaining passengers were sold into slavery.

Sultan Ibrahim was enraged. Furious and grieving, he summoned the ambassadors of France, England, and Venice to determine if they had played any role in this violation. They denied all involvement, asserting Malta’s independence.

The Sultan considered immediate retaliation against Malta. But his Grand Vizier had a more strategic suggestion—one that would shift the course of Mediterranean history.

From Malta to Crete: A Deceptive Invasion Begins

The Vizier claimed that the Maltese had stopped in Venetian-ruled Crete to resupply, and—more damningly—that the Venetians had knowingly assisted the Maltese in capturing the Sultan’s family. Whether true or not, it was enough to convince Sultan Ibrahim.

The plan was set in motion: Crete would be punished first. Not Malta.

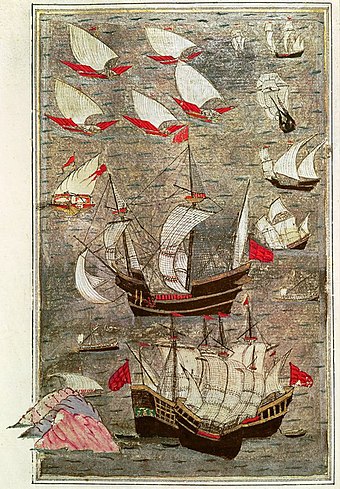

In secret, a massive Ottoman armada of 440 ships and 60,000 men was assembled—the largest of its kind at the time. The armada’s supposed destination? Malta. This ruse was critical to the Vizier’s plan. To make it believable, the admiral was instructed to dock at Kythera for sugar and coffee and spread the word that Malta was their target.

Even the Venetian governor in Chania was fooled, relaxing defenses based on the Kythera report. Meanwhile, the Ottomans anchored at Navarino, in the Peloponnese, lying in wait to deepen the deception.

June 12, 1645: The Ottoman Fleet Turns to Crete

On the morning of June 12, 1645, the entire fleet abruptly changed course and sailed toward Kolymbari Bay, just west of Chania. The sight of 440 Ottoman warships entering the bay must have been both awe-inspiring and terrifying.

And yet—not a single cannon was fired.

The Venetian commanders, taken completely by surprise, chose not to engage. Instead, they abandoned their posts in a desperate attempt to save their own lives.

The Hero of Thodorou: Vlasos Julio’s Last Stand

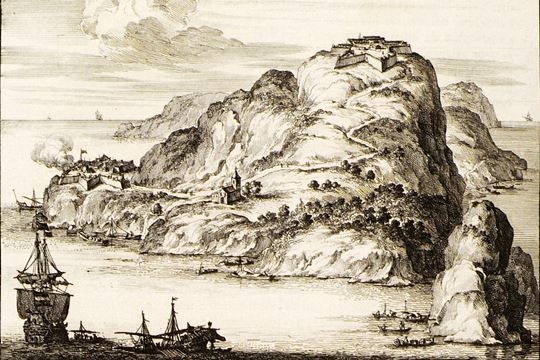

The only resistance came from Thodorou Islet, just 4 kilometers off Chania’s coast. This tiny island held two Venetian fortresses and a small garrison led by Vlasos Julio, the general in charge.

Faced with overwhelming odds, Julio and his 65 men fought valiantly, firing at the armada in a last-ditch effort to stall the invasion. But the Ottoman cannons, far superior in range and power, quickly reduced the fortresses to rubble.

Knowing defeat was certain, Julio made an unthinkable decision. Rather than surrender, he and his remaining men ignited the fort’s remaining gunpowder stores, sacrificing their lives—and taking 500 Janissaries with them.

Thodorou: The Gateway to Crete’s Fall

Julio’s self-sacrifice delayed—but did not stop—the Ottoman conquest. With Thodorou silenced, the Ottomans swiftly moved inland. Within days, Chania fell, and the 253-year Ottoman rule of Crete began.

What started as a misjudged naval capture by Malta became one of the most significant events in Cretan history. And it was a single man on a tiny island who embodied the last spark of resistance, setting the standard for bravery in the face of doom.

Conclusion: Legacy of Strategy, Deception, and Courage

The 1645 Ottoman conquest of Crete was not just a military campaign—it was a masterclass in psychological warfare and political manipulation. The Grand Vizier’s phantom route, the false trail to Malta, and the quiet weeks in Navarino led to one of the most dramatic ambushes in early modern history.

And while Crete fell, the story of Vlasos Julio and the Battle of Thodorou reminds us that sometimes, the greatest resistance can come from the smallest places.

Vincenzo Cornaros’ timeless epic still echoes through the verses, voices, and hearts of Crete.

For many years I’ve lived elsewhere, away from Crete and Greece. When I’m gone for a long time…

In 1769, Crete was bleeding under the crushing weight of Ottoman oppression…