The Painter from Crete Who Became El Greco

From Chandaka to the Canvases of Europe

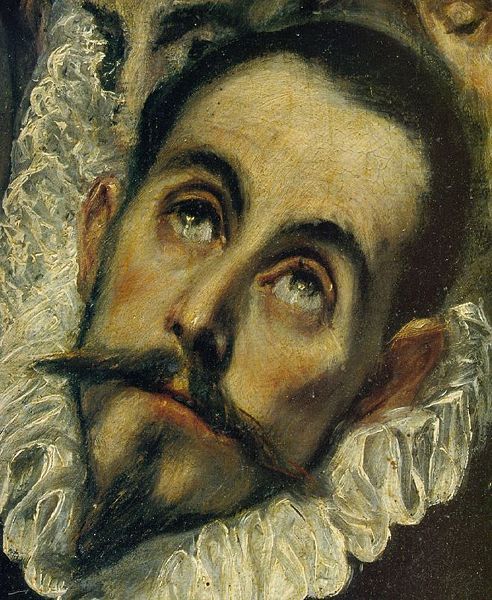

When I was a child, flipping through an old art book, I stopped cold at one image: the eyes of Christ gazing upward in haunting prayer. The painting was The Disrobing of Christ, and the artist, I would later learn, was Domenikos Theotokopoulos — the man the world now knows as El Greco.

What amazed me most? He, too, was from Crete.

A Cretan Beginning

Born in 1541 in Chandaka (present-day Heraklion), Domenikos was the son of a tax collector. After his father’s death, his older brother Manousos helped guide him. Their family’s wealth gave Domenikos a solid education and access to training in ecclesiastical art — a fusion of Byzantine and Western techniques that flourished in Crete under Venetian rule.

By age 22, he was already “Maestro Domenigo,” with a recorded painting sale of 700 ducats — proof of his emerging genius.

Venice, Rome, and a Clash with Michelangelo

In 1567, he set sail for Venice, joining the workshop of the legendary Titian and engaging with Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, whose circle included Europe’s most enlightened artists and thinkers.

Next came Rome, where El Greco was deeply influenced by Michelangelo and Raphael — yet famously claimed he could paint better scenes than Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. The art world did not appreciate his candor, and he was soon asked to leave.

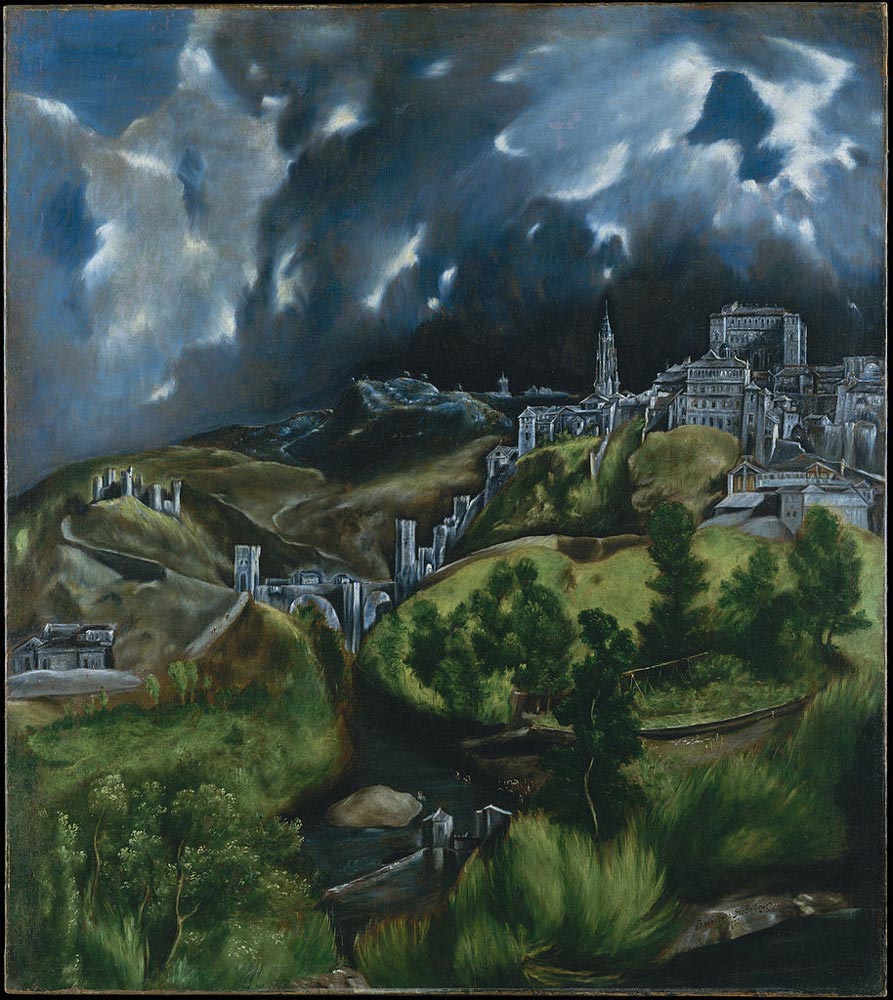

Toledo: Where the Style Was Born

It was in Toledo, Spain, that El Greco found his artistic home. He remained there for the final 37 years of his life, developing the elongated forms, mystical light, and spiritual intensity that made his style unmistakable.

He fathered a son, Jorge Manuel Theotokopoulos, with Jeronima de Las Cuevas, though they never married. His nickname, “El Greco” (“The Greek”), followed him from Italy and stuck — a mark of his origin that he embraced.

Every painting was signed with pride:

“Created by the Cretan Domenikos Theotokopoulos.”

Crete in His Heart, Always

Though he never returned, Crete was never far from his thoughts. In later life, he reflected:

“In Crete I would dream of Italy, in Italy I would dream of Spain, but now I believe I must begin to wish myself back to my homeland, Crete.”

He remained close with his Greek friends and family — and left behind not only paintings, but cultural pride and spiritual truth.

A Lasting Legacy

- Pablo Picasso called him his “Father.”

- Nikos Kazantzakis, author of Zorba the Greek, referred to him as his “Grandfather,” writing Report to Greco as a spiritual dialogue with the painter.

- Art critics credit El Greco as a precursor to Expressionism and Cubism, bridging the Renaissance and modern art with a voice that was uniquely his own.

Standing Before the Masterpiece

Seeing The Disrobing of Christ in person left me breathless. The color, the scale, the divine elongation of the figures — it was as if the heavens had touched the canvas.

Through his work, El Greco gave the world not just art, but permission to feel deeply, to create boldly, and to remain true to one’s roots — no matter how far we travel.

The Monster in the Labyrinth…

The Kalisperides or Hainides: Crete’s First Resistance Fighters

Crete Dreaming: A Return to the Island of Sun, Sea, and Soul